Believeco

Creating, evolving and propelling brand-audience relationships.

Small shops don’t have the resources.

Big shops don’t have the soul.

That’s why we’re here.”

Four leading independent agencies, with deep experience and roots across Canada, came together to bring the best of independence and relationship-first service at scale. We have expertise in multiple industries, from financial institutions to automotive and from sports to aerospace, and have dedicated verticals in health and food and beverage. We’re here to transform what an agency can do, and how they do it. Learn more about our story.

This is what we mean by full service

No agency website is complete without a laundry list of capabilities (see below!) More importantly, we place a tremendous value on integration – across channels, between teams and with our clients. We collaborate constantly, allowing expertise and insights to be shared. We know we’re better together.

Expertise

- Strategy and analytics

- Online video

- Broadcast TV

- SEO and SEM

- Public and media relations

- Packaging

- Creative and design

- Animation

- Digital and social

- API and platform integration

- Experiential marketing

- Production

- Audience identification

- Content marketing

- E-commerce

- AR and VR

- Motion graphics

- Market positioning

- Product launch

- Branding

- Media planning and buying

- UX/UI

- Photography

Have a question? Looking for a partner?

Want a great career? Get in touch!

Our work

There’s nothing better than releasing our creations out into the wild! Check out some of our success stories.

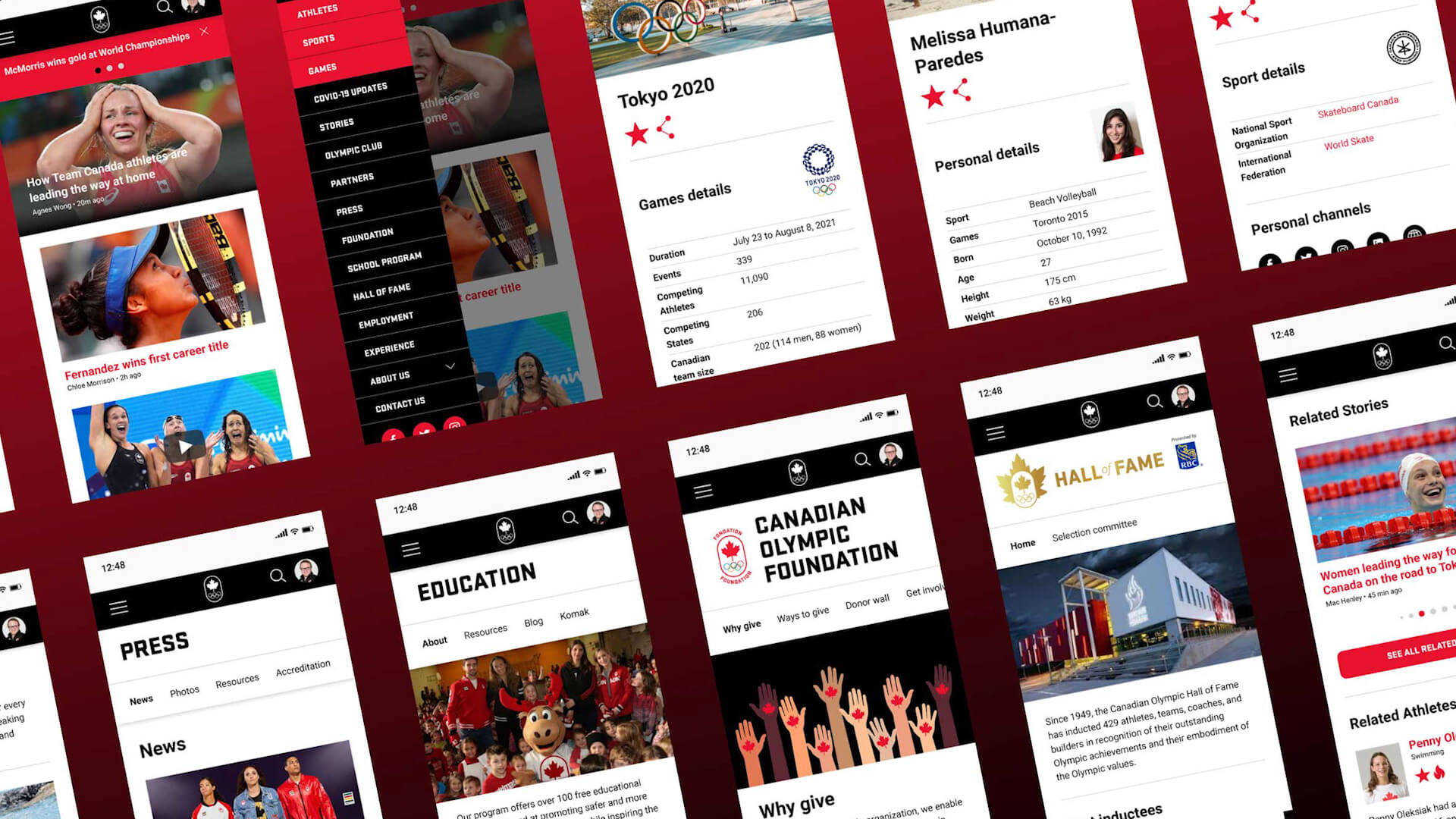

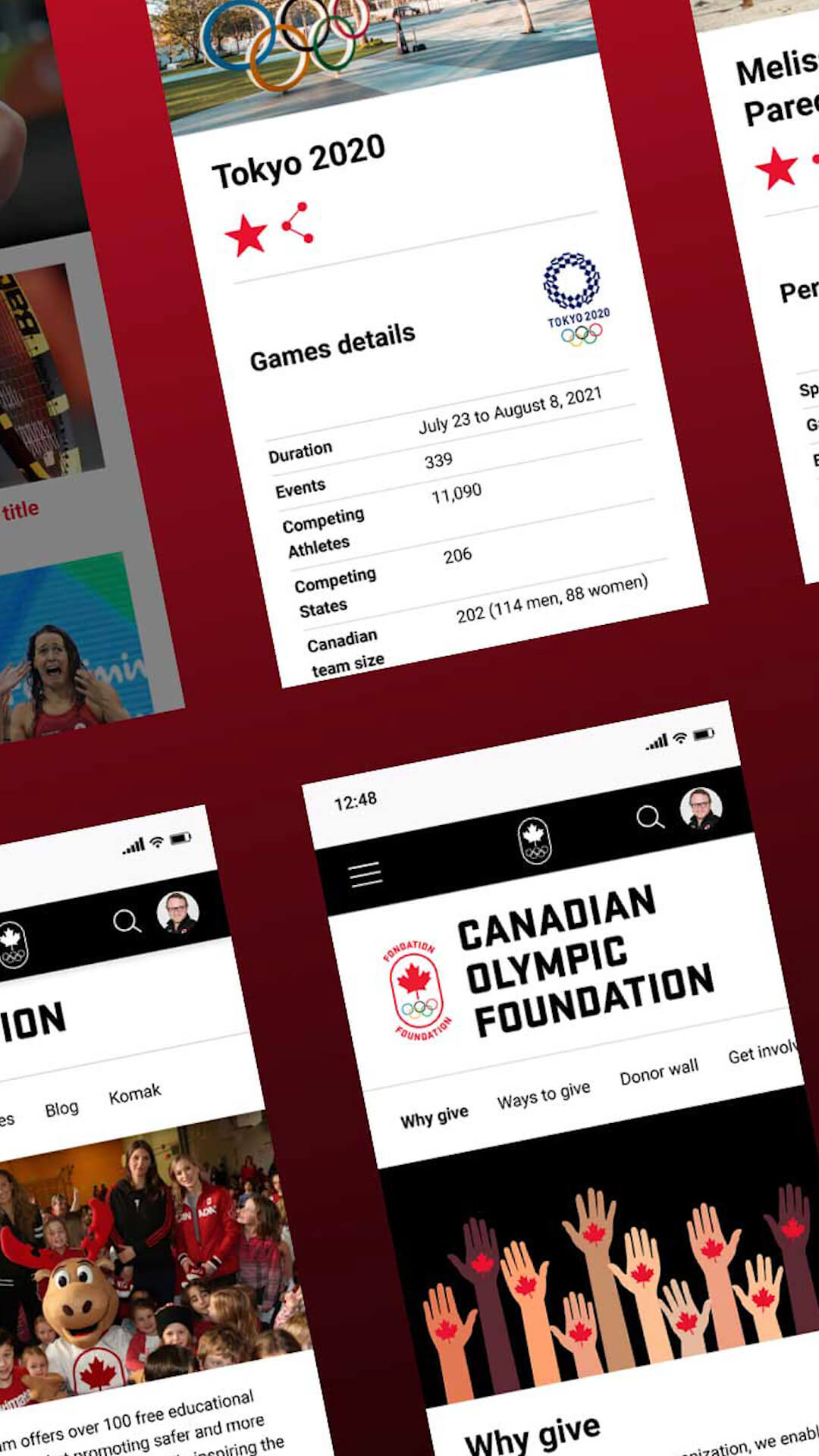

Engaging Team Canada fans coast to coast.

Canadian Olympic Committee

A complete redesign and optimization of the Canadian Olympic Committee’s digital assets have led to dramatic growth in fan adoption and engagement — becoming the home for Canadians to learn about, engage with and cheer on Team Canada.

Keeping frozen potatoes hot.

Cavendish Farms

We nurture Cavendish Farms’ brand-audience relationship through a relevant and flexible social media strategy. It’s led to a lasting partnership and work in multiple facets of their business.

Bringing dairy back.

Alberta Milk

The Smash Milk campaign reconnected Millennial and Gen Z women with dairy. Vibrant, exciting and irreverent creative highlighted the wide variety of products, and the joys of eating and drinking dairy.

Insights

News

Announcement

Believeco:Partners (BCP), one of North America’s leading independent strategic marketing, communications and advisory firms, today announced veteran entrepreneur and global corporate strategist Mario Simon as its Chief Executive Officer. Beginning February 20, Simon will lead the agency’s 300-plus team across more than 10 offices in North America. Welcome Mario!

Announcement

Laura Lewandowski brings insight and leadership to the growing Believeco team as EVP Media

Recognition

As good as gold: Believeco wins big at CMAs

Announcement

Announcement

Arlene Dickinson has brought together six of Canada’s leading independent agencies to bring North American businesses independence at scale. Read her letter.